How Doctors Can Help Prevent Gun Deaths

Guns are a major cause of accidental death and suicide, yet most physicians still don’t treat them like a health hazard.

Two people died in a mass shooting in Florida this week, after the worst mass shooting in U.S. history happened at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando just 43 days ago, which itself was the 15th mass shooting in Florida this year.

The frequency of mass shootings, while horrifying, obscures the banality of everyday gun violence in the U.S. Specifically, that far more people are killed in gun suicides and accidents than in homicides.

Guns are primarily suicide machines. There were 21,334 firearm suicides in 2014, according to the CDC, but people use guns to justifiably kill someone in self-defense only about 250 times each year. Half of Americans who kill themselves use a gun.

Having a gun in the home is also strongly correlated with accidental shootings. As I’ve written, about 1.7 million children live in homes with guns that aren’t safely stored. Toddlers alone have shot at least 23 people this year.

Most unintentional shootings of children happen in homes where guns are legally owned, but not stored safely, and 70 percent of them could have been prevented if the gun had been stored safely.

In its call last year to consider gun violence “a public health imperative,” the American Academy of Pediatrics noted that among people younger than 24 “Gun injuries cause twice as many deaths as cancer, five times as many deaths as heart disease, and 15 times as many deaths as infections. The United States has the highest rate of firearm-related deaths among high-income countries,”*

This is precisely where the health-care system can play a role in curbing gun deaths. Research shows that counseling by doctors can help promote safe gun storage—which is why most medical groups recommend that doctors ask patients whether they have guns, and if so, how they’re stored.

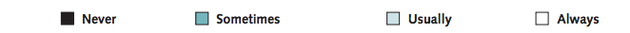

A new survey of 3,914 Americans, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, found that two-thirds said it was at least sometimes appropriate for providers to have this kind of discussion with patients. Among firearm owners, about half said these conversations were sometimes appropriate.

Despite the seeming openness on the part of patients, few doctors counsel people about gun safety. Their own apprehension and a confusing legal landscape keep them from asking patients about guns just like they would about seat-belts, poison control, or nutrition.

According to a 2014 survey of internists, the overwhelming majority of doctors—85 percent—agree that firearm safety is a public-health issue, but 58 percent nonetheless said they never ask whether patients have guns in their homes. A meta-analysis published last year found that “providers rarely screen or counsel their patients—even high-risk patients—about firearm safety.”

To make matters worse, Florida, home of both this week’s Ft. Myers shooting, last month’s Orlando nightclub shooting, and about 2,000 other yearly gun deaths, passed a law five years ago preventing doctors from asking their patients about gun ownership. The law, called the Firearms Owners’ Privacy Act and sometimes referred to as “Docs vs. Glocks,” allows doctors to ask their patients about guns only if they have a “legitimate safety concern.” Doctors who don’t follow the rule could be fined or lose their licenses.

Many doctors’ groups say the law is against their First-Amendment rights, and the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta is currently weighing the law’s constitutionality. But at least 10 other states have introduced similar measures in recent years.

Asking about guns seems to make some doctors uncomfortable. Most doctors don’t own guns themselves, and laws like those in Florida and elsewhere may prompt fears that they’re doing something illegal. (For example, the Affordable Care Act prohibits medical professionals from recording information about the presence of firearms in a patient’s home, as the Trace’s Kate Masters points out, but not from asking about firearm ownership).

Patient resistance might be a factor, too: In the Annals of Internal Medicine study, a third of people said it was “never appropriate” for doctors to ask about guns. Doctors, already short on face time, might worry about needlessly offending their patients.

“Conversations about gun safety between providers and patients should be nonjudgmental, educational, and focused on improving the health and safety of the patient and those around him or her,” the lead study author, Marian Betz of the University of Colorado in Aurora, told Reuters. “Unfortunately, the larger political debate over gun control laws can spill over into health-care settings.”

In an editorial on the importance of physician gun-counseling published in the Journal of the American Medical Association last year, Betz and a colleague wrote that providers shouldn’t let their discomfort stand in the way.

“At times, clinicians may feel uncomfortable or uninformed when discussing certain subjects, and may disagree with a patient’s choices or beliefs,” they write. “However, this discomfort or disagreement cannot justify either offensive condescension or silent inaction.”

* This article has been updated to clarify that the study the AAP press release referenced measured cancer deaths among people under the age of 24.